Hamlet can be played as a melodrama, or as a tragedy; the two are not entirely immiscible, but the grandiosity and the melancholy of one of Shakespeare’s most famous plays leaves it often to interpretation. There have been numerous film adaptations and adaptors: Laurence Olivier (1946), Grigori Kozintsev (1964), Tony Richardson (1969), Ethan Hawke (2000). The tale of the downfall of the prince of Denmark and his family contains the same classic messages and timeless themes that initially made it famous, and today we take a look at Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet (1996).

It is a notable film firstly because it is the first unabridged theatrical version of the play, running at about 4 hours, and with the original dialogue; I know, I can hear the groans. It sounds like a nightmare for anyone other than a theater student or an English major. The other reason is that it was the last film – apart from Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master (2012) – to be shot in Panavision Super 70mm film. We will go into why that is important in a moment.

Because the film is so long, I’m splitting up my commentary into two general parts: Composition and Color of Part 1 (~2 hour mark) and then Part 2.

Composition

70 mm film is special. Standard motion picture format is 35 – 65mm, and the higher the millimeter, of course, the higher the resolution. Panavision Super 70 is a whole other animal from the literal types of film we see today; it was the same type of film used to shoot Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, and West Side Story. It was also featured in Inception, Samsara, and The Dark Knight Rises. Quentin Tarantino famously used Panavision’s other 70mm lenses, the Ultra 70, in The Hateful Eight, similar to its predecessor, Ben Hur.

Hamlet was filmed entirely on Panavision Super 70. This comes especially useful in wide shots, long single takes. Wide angle lenses let the viewer take in the full shot, and see the essence of the setting in its entirety, and it also gives a more inclusive sense of depth heightening colors and adding detail one normally wouldn’t see in a feature film. It is an indulgent way to introduce moviegoers to what their watching, and Hamlet, at its core, is an indulgent film, telling the tale of luxury gone to spoil.

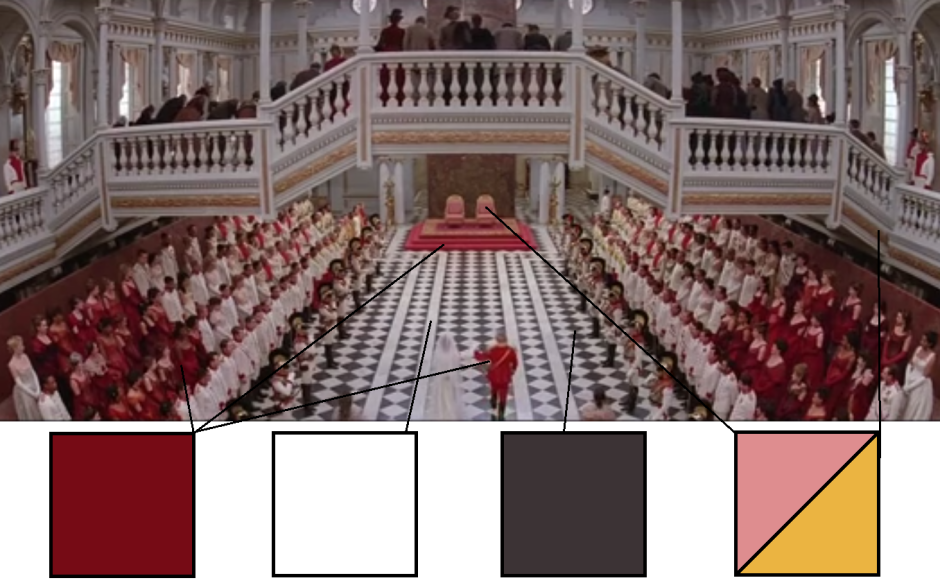

Take the first major scene for example, the wedding of Claudius (Derek Jacobi) and Gertrude (Julie Christie). We open on a wife shot of the hall – shot an Blenheim Palace – full of court members and choirs as the newlyweds walk down the aisle to their thrones to rapturous music. Everyone below the viewing gallery is dressed in bright colors – red, white, pastel pinks – and then there’s Hamlet (Kenneth Branagh), looking like a chic Hot Topic catalog.

The camera does not reveal him until the very end of Claudius’ speech, instead switching viewpoints from straight ahead and from above, as if we look down the aisle and then below from the gallery. We look everywhere but at Hamlet himself, and it requires a special panning shot to reveal him, solitary, behind rows of well-wishers. It is a beautiful establishing shot – he is slightly to the left of center, wedged between the stands and the wall, dressed in all black, still in mourning for his father. This shot gives us his nature, and his state of mind, all at once; separate, solemn, unwilling to participate in the proceedings.

He sports a high collar – conservative – and bright platinum Danish hair, making him stand out like a ghost against his dark clothes. He immediately presents as a dramatic figure, and our eyes are drawn immediately to him, more so than Gertrude or Claudius, who blend in among the ladies of the court and the soldiers’ uniforms. He speaks lowly, pained, and wears a constant frown.

Perhaps my favorite shot in the film is at the very beginning: confetti rains down from the rafters, the people cheer, and Hamlet stands alone on the throne pedestal before he commences his famous line – no, the other one – “the funeral baked meats did coldly furnish the marriage tables”.

This shot tells us everything we need to know; wide in scope, it gives us the full empty luxurious throne room, and Hamlet, right in the middle, black and unmoving among the celebration, disgusted by its lavishness.

A few scenes later, we see Ophelia (Kate Winslet) saying goodbye to her brother Laertes, who warns her to be cautious of Hamlet’s romantic intentions. We follow on a tracking shot along side them as they walk, giving us a full view of Elsinore behind them; what this does is it gives us a true portrait of how large the castle is, and the power that lies behind the Hamlets’ throne – in short, it reveals why Claudius wanted to betray and kill his own brother, for the gold and the glory that Elsinore represents.

When the ghost of Hamlet’s father appears, there is one distinct shot as he speaks to him:

Look at how his face only composes one quarter of the shot, yet he dominates almost the whole thing. He looks dangerous, otherworldly: his eyes are an unnatural blue, his visor protruding our, his face lined on the side by a sharp, curving ventail that looks almost like pincers. He looks scary because he is presented that way, taking up most of the frame in hard, dark armor and precise angles.

See as well at how Hamlet mirrors the shot, taking up the other side and leaving an empty space where his father’s ghost speaks in the next frame:

They talk about his father’s murder, and speaking as equals, on par with each other if the shot were combined. It creates a sense of fluidity, as if they are a continuum, and Hamlet swears to take revenge on his father’s killer. The scene contains a number of mirrored shots, matching Hamlet and his father; this gives us the sense of balance – his father’s curse has passed on to be burdened by him, and indeed, he spends the film as a ghost of the carefree man he was. His father’s death deeply affected him, and he falls away from his loveblindness with Ophelia, blurring the lines between feigned madness and true insanity and paranoia.

Color

The costuming merited a nomination for Best Costume Design at the 69th Annual Oscar Awards, but lost out to The English Patient, an Academy darling (9 wins out of 12 total nominations). If we take a look at the color schemes present in the movie, we see they present often, and consistently, beginning with the wedding scene:

All of these major colors return, most notably the red, white, and black.

Of course, black is the most noticeable, as only Hamlet appears in full dark ensemble. It is the color of mourning and grief, and keeps us reminded of the pallor of death that haunts Elsinore, partly in the form of Hamlet himself.

Next we have red: red is the color of the dias, the color of royalty; Claudius is shown wearing green until he ascends to the throne, and he and Gertrude are featured heavily in red, the color of their station. Red is also the color of the head troubadour (Charlton Heston), who inspires Hamlet to create his “play within a play” trap. As a visual choice, red instantly draws our attention; it is a vibrant, eye-catching color. It tells us ‘pay attention’, singles out characters in a scene, and makes us impart importance on them; think now to the famous ‘red dress’ girl in Schindler’s List, standing out brilliantly against the black and white.

In contrast, white is used almost misleadingly. One would be tempted to say it represents innocence, but that isn’t quite correct with this film; plenty of characters wear white, and the effect this has generally is that it makes them invisible, background performers. The setting features white frequently: the parquet floor of the throne room, the throne room itself, the snowy grounds of the castle. Look at how white is used in this shot:

Amid these fencers is Hamlet, laying down some foreshadowing for later. They are nearly indistinguishable from the deadened, snowy surroundings, but Hamlet isn’t. This costuming is deliberate; it makes our eye draw to him, because he contrasts against the background so strongly.

Amid these fencers is Hamlet, laying down some foreshadowing for later. They are nearly indistinguishable from the deadened, snowy surroundings, but Hamlet isn’t. This costuming is deliberate; it makes our eye draw to him, because he contrasts against the background so strongly.

The color green is used prominently as well. It is the color of the naive and the subordinate, often featured on officers in the background or of a lower rank than the king. Ophelia initally appears in an off-white pistachio color in Laertes’ farewell, and in the next scene her father chides her: “you speak like a green girl”, meaning she’s speaking naively.

Ophelia (so far in part 1) has only worn green in this one scene. Why? Because it is the scene where she must be totally subordinate to her father’s wishes; he does not want her to see Hamlet and prolong his perceived use of her. At the end of the scene, she admits ‘I will obey’, thus subjugating herself to the power of her father.

Hamlet is a marathon in itself; as a play, it can be easy to lose track of yourself in Shakespeare’s intricate turns of phrase and attention to detail, especially with its run time. But Branagh as a director understands this, and lays bread crumbs here and there for the viewer to follow, from attention to a consistent color palette and long, wide shots that allow us to breath in moments of tense confrontation and feigned lunacy.

We will follow these themes tomorrow, with “Hamlet: Color and Composition: Part II”